Two React MVVM patterns

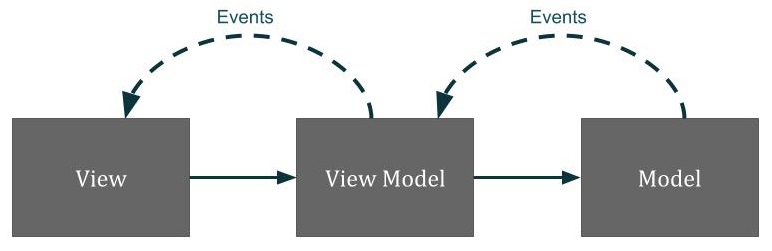

24 March 2018In this post we’ll talk about two MVVM-compatible architectural patterns for React aiming at explaining how a user action all the way deep inside a nested view in the corner of a web app can affect a different view on the other side of the app.

For example, say you you split your application into two main halves, each with their own controls and features. Say that clicking a particular button in one of the views will render a new view in the other main half.

… Other than leveraging the model

If you adopt MVVM as the main way to drive your application, the simplest answer is to let the core application model drive every view. Selecting a control in one of your views eventually changes the core model, your other view is ultimately driven by such changes and so it responds by re-rendering as appropriate. This means you only need to ensure your core model can support modeling this type of user action.

The obvious limitation to this approach is that sometimes the event action does not cause a change in your core model itself, but only affects what is shown to the user. For this reason it perhaps does not belong to the core model, which is meant to reflect the implementation independent and view independent state and logic of your application.

For example, let’s assume the button your user clicked is really only meant to navigate them to another view, and does not have any significant side effect on the model (i.e., does not change the state of your transactions, does not change how the user relates to other abstract entities in your model such as other users etc.) In this case, the user action has no effect on the model, so there is no model change that could drive your views1.

After all, a view is only a projection on the core model, and this is only meant to describe the core state of the application. Anything outside of it should be handled by the view model or view layer. So the real question is how can you handle relaying user actions without using the model? We’ll propose two different approaches:

-

The hierarchy approach

-

The event bus approach

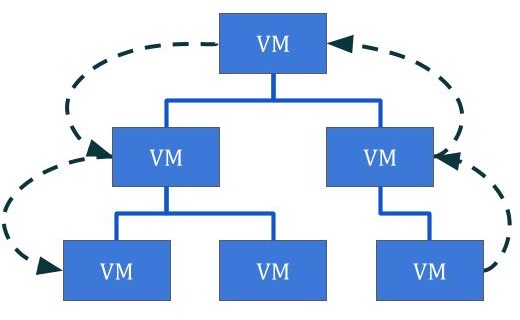

The hierarchy approach

The structure of your application is a hierarchy of React components, the structure of your view models (or the way you arrange them at runtime) is going to mirror this hierarchy at least to some extent. Some of the more complex view models view are likely to be composed of multiple sub view models, one for each of the sub views of your more complex views.

Sub-view models can expose events (via subscription/observable based patterns) so that their parent view model can be made aware of actions or other changes as they happen without creating symmetric dependencies between your view models at runtime (this mirrors a React pattern where parent views are aware of actions/changes in their children through callbacks passed down as props.)

This way you can relay the action to the first common parent the two main views share, when this handles the event from one of your views it will know which view to change. Effectively, in this pattern you pick up the click event and bubble it (in some form) to the root of your application which then forwards it to the view that should handle it.

Limitations

Using this approach requires explicitly handling each individual event up and down the hierarchy, this can make your view models more and more complex as you add more features, and it can make it very easy to lose track of where exactly events are meant to be handled and where they originate when this pattern is applied to multiple controls.

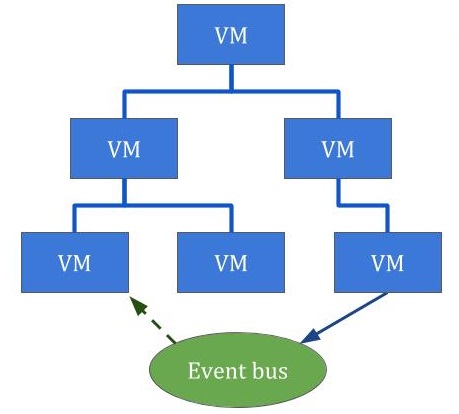

The event bus approach

Again, a user action is a sort of event which you need to relay from the view where this originates to the view that will receive it. Rather than explicitly forwarding this event up and down the view hierarchy, you can define an “event bus” of sorts: a module that the view will invoke when the event has been received that will relay it. Inject a reference to this module into both the view where the event originates and the view that is meant to receive it.

Note that the extremely popular “flux” pattern is basically a generalization of this approach where everything is forwarded to a global event bus and any part of the application can subscribe to events from the bus.

Limitations

With this approach, you still need to explicitly define and wire up your event relays throughout your view models. However this removes the need to define explicit handling for various types of events and actions throughout the hierarchy. It also reduces the potential confusion arising from having events referenced throughout the hierarchy but only used in the originator and receiver.

Conclusion

I believe I’ve already given away which of the approaches I prefer. Event buses allow for neater, less verbose implementations with less boilerplate and leave the core model alone. They are relatively straightforward to implement on top of any observable pattern. Finally, adopting ad-hoc event relays instead of relying on a global event bus avoids a form of implicit global state. Really, whether this is a good or a bad thing comes down to whether having less boilerplate is worth not having an explicit mapping of your events to event relays.

If you use a global bus you cannot prevent parts of your application that are not supposed to know about certain events from subscribing to them (this maybe doesn’t sound like a terrible issue, but in larger and more complex projects written by multiple hands issues of this sort arise all the time.) On the other hand, if you use ad-hoc event relays you prevent events (and therefore state) from “leaking out” to places they do not belong to, at the cost of more boilerplate: you will need to explicitly inject your event relay instances where needed.

Further Reading

- Flux core concepts. https://github.com/facebook/flux/tree/master/examples/flux-concepts

-

Whether navigation state should or should not affect the state of the model is arguably more of an architectural concern than a non-controversial example of something that should not be modeled by the core model. It really depends on what you consider to be the core state abstract state of your application. ↩